Patient Type 1

Masticatory Muscle Disorders

There is very little potential risk associated with Type I TMDs. However, response to treatment can vary greatly, determined by whether appropriate treatment strategies are used. With disorders involving only muscles, an anterior-contact/deprogrammer type appliance may be used for night-time or short-term wear. When a full coverage occlusal appliance is used, two clinical objectives will make a significant difference in patient response to occlusal appliance treatment. First, and most importantly, an occlusal appliance should provide uniform posterior occlusal contact, preferably with cusp tips against a flat surface. Second, the occlusal appliance should allow the potential for mandibular reposturing to a musculoskeletal condylar position (Okeson). This means that anterior guidance should be quite shallow, rather than steep. Nothing on the appliance should contribute to the patient’s jaw being “locked in” or directed to a fixed position. This type of appliance is generally referred to as a “stabilization” appliance. Dawson uses the term, “permissive”, to describe this appliance design. This type of appliance can also be used as a deprogramer. Even if there appears to be no involvement of the TM joints, some change in jaw posture will often be seen as a result of appliance wear as the condyles are seated by the elevator muscles. Because closure into the native occlusion (centric occlusion) can cause a deflection of the jaw that may not otherwise have been detected, wearing a “permissive” appliance will mask this deflection and allow the jaw to close without any influence from the teeth. If the joints are able to achieve a more stable musculoskeletal condylar position (Okeson), this change in jaw posture may be desirable. If this type of change is seen, knowing how to properly manage the resulting occlusal effects is crucial.

Following initial fitting, initial occlusal adjustment of the stabilization appliance should be done to the border position, with the patient in a reclined position. This should be followed by adjustment to an upright, relaxed-jaw posture without any hands-on jaw guidance. Follow-up adjustments should also be done with the patient sitting upright and no jaw manipulation is indicated. The patient should be instructed to close lightly with the jaw completely relaxed. This encourages a muscularly-determined (musculoskeletal – Okeson) condylar position. The patient is instructed to tap lightly on thin marking ribbon in this relaxed jaw posture. Adjustments are made, using this approach, until all posterior contacts are reestablished. Although clinicians may differ regarding hours of appliance wear, there is broad agreement that night time wear is, at a minimum, essential.

Follow-up adjustments should be done in the same, non-manipulated manner and should occur at fairly frequent intervals as long as any change in tooth contact on the appliance is seen from visit to visit. As changes on the appliance decrease between visits, time between visits can be increased. When symptoms are significantly reduced or eliminated and little or no change in tooth contact is seen on the appliance from visit to visit, the patient can be considered “stable”. If achieving this level of stability and decrease in symptoms does not seem to be progressing, full-time wear may need to be considered. If, after wearing the appliance for some period of time, the patient is aware of changes in the native dental occlusion when the appliance is not in the mouth, the nature of this occlusal discrepancy should be evaluated using mounted models and appropriate occlusal treatment options should be considered.

Patient Type 2

Capsular and Attachment Tissue Disorders

(Joint Sprain and/or Joint Hypermobility Disorders)

Capsular pain and inflammation are fairly common. Although these can potentially result from direct injury, such as trauma to the joint, a common contributor is likely to be parafunction, grinding of the teeth, which puts stress on the lateral joint capsule. Deflective occlusal contacts may also load the joint capsule adversely, contributing to capsular pain. When there is joint pain of any kind, there is likely to also be muscle tightness and pain resulting from reflex muscle splinting (co-contraction).

The clinical approach to this patient type is very similar to Type I. Likewise, there is very little risk associated with capsular pain and accompanying muscle pain, so long as it can be confirmed that there is no other structural damage to the joints, such as an internal derangement. By using a “permissive” stabilization appliance, as described above, uniform posterior occlusal contact is achieved and the potential for lateral loading of the joints is reduced or eliminated. Again, adjustments to the appliance should be done in the manner described above and at a frequency based on the changes that are seen on the appliance. Evidence of improvement will include a significant reduction of subjective symptoms and evidence of a stable jaw position, indicated by a lack of change in occlusal contacts on the appliance from visit to visit. If the majority of bruxism is occurring during sleep, night-time wear of the appliance may prove effective. However, full-time wear can be considered if improvement in symptoms is not occurring, increased hours of wear should be considered. With any TM joint inflammation, the use of anti-inflammatory medications may be appropriate.

Patient Type 3

Disc Displacement with Reduction – No Pain

(minimal or no disc interference)

Disc displacement with reduction is an extremely common phenomenon. Studies using history and exam only have demonstrated that between 30 - 40% of the general population has clicking and popping of the TM joints. This finding is nearly always indicative of a disc displacement. In studies that have also used MRI imaging on general population groups (non-patients), the prevalence rate increases to somewhere around 75 – 80% of the general population, with women represented more frequently than men. It is fortunate that most of these individuals do not seek nor need treatment and seem to go on through life with this condition. Most apparently go to their grave with it.

This frequency of occurrence, however, can easily lead to complacency about a finding of sounds from the TM joints. A Type 3 patient (clicking/popping without joint pain) may require no treatment whatever, so long as there is no indication of catching. This would certainly be the most common scenario. If joint pain is absent but there is muscle pain, treatment would be much like with a Type I TMD. However, mild clicking and popping that is progressively getting louder, in spite of an absence of pain, is almost certainly indicative of a condition that is progressing and may either become painful or, more likely, may progress to catching (Type 4). Therefore, even in the absence of joint pain, when there is evidence of this type of progression, appropriate early intervention is advisable.

If a Type 3 patient who demonstrates clicking/popping together with pain from the TM joint(s) will also benefit from a stabilization appliance that provides the potential for re-posturing of the mandible, as described above. So long as there is no evidence of catching (Type 4), most Type 3 patients will respond very well to appropriate occlusal appliance therapy. Changes in joint position will occur commonly with Type 3 patients and attention to this and the possible need for occlusal management must be kept in mind when undertaking treatment of these patients.

It should be quite apparent that treatment of a Type 3 patient requires not only some careful questioning (is clicking, popping, catching progressing?), but also a fairly simple but critical examination for joint pain. This is where the screening procedure really begins to pay off (see “Early Recognition of Temporomandibular Disorders”).

Patient Type 4

Disc Displacement with Reduction – With Pain

(minimal or no disc interference)

Disc displacement with reduction is an extremely common phenomenon. Studies using history and exam only have demonstrated that between 30 - 40% of the general population has clicking and popping of the TM joints. This finding is nearly always indicative of a disc displacement. In studies that have also used MRI imaging on general population groups (non-patients), the prevalence rate increases to somewhere around 75 – 80% of the general population, with women represented more frequently than men. It is fortunate that most of these individuals do not seek nor need treatment and seem to go on through life with this condition. Most apparently go to their grave with it.

This frequency of occurrence, however, can easily lead to complacency about a finding of sounds from the TM joints. A Type 3 patient (clicking/popping without joint pain) may require no treatment whatever, so long as there is no indication of catching. This would certainly be the most common scenario. If joint pain is absent but there is muscle pain, treatment would be much like with a Type I TMD. However, mild clicking and popping that is progressively getting louder, in spite of an absence of pain, is almost certainly indicative of a condition that is progressing and may either become painful (Type 4) or, more likely, may progress to catching (Type 5). Therefore, even in the absence of joint pain, when there is evidence of this type of progression, appropriate early intervention is advisable.

A Type 4 patient who demonstrates clicking/popping together with pain from the TM joint(s) will also benefit from a stabilization appliance that provides the potential for re-posturing of the mandible, as described above. So long as there is no evidence of catching (Type 5), most Type 4 patients will respond very well to appropriate occlusal appliance therapy. Changes in joint position will occur commonly with Type 4 patients and attention to this and the possible need for occlusal management must be kept in mind when undertaking treatment of these patients.

It should be quite apparent that treatment of a Type 4 patient requires not only some careful questioning (is clicking, popping, catching progressing?), but also a fairly simple but critical examination for joint pain. This is where the screening procedure really begins to pay off (see “Early Recognition of Temporomandibular Disorders”).

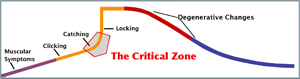

Variability, Progression, and the Critical Zone

The Critical Zone

This term is used to designate an area in the continuum of TM disorders that can rapidly move from risk-free to high-risk conditions. Being able to determine whether a patient’s TM disorder has entered the Critical Zone requires that the patient be carefully screened by means of the screening history and the screening exam. If this has not been done, the patient can appear to have a relatively minor condition but the condition can potentially worsen very quickly with very unfavorable outcomes.

Inappropriate treatment may accelerate this progression. In discussing Type 4, above, if the clicking/popping involves even mild catching, or if the clicking/popping has been getting progressively more frequent or louder over time, this is evidence of progression and the joint condition may rapidly move from Type 4 to Type 5 (catching) or even to Type 6 (locking) if the wrong approach to treatment is undertaken. A Type 4 patient may be in the Critical Zone, in spite of an absence of joint pain.

The significant point that needs to be understood is that if the dentist decides to treat a Type 4 patient, they need to be very sure that there is little chance that the treatment will not promote a progression to a more advanced condition. That having been said, if appropriate treatment is provided, it is fairly unlikely that the patient’s condition will worsen.

Patient Type 5

Disc Catching with Reduction

(with or without pain)

Patients who are experiencing catching in one or both of their TM joints are usually quite aware of it, but may not volunteer that they have such a condition if there is no associated pain and/or they are easily able to overcome it with a simple movement of their jaw. Again, the importance of the screening questionnaire must be emphasized. If the patient is asked about catching in their TM joints, some will recognize it as catching and others may describe it somewhat differently. Not uncommonly they will say that it feels like their jaw is “going out” or is out of place. Therefore, questioning should be approached in a manner that allows them to provide their own descriptive terminology.

As just mentioned, early catching may be easily overcome and patients may largely ignore it. At this stage, the catching may not significantly interfere with function. However, early (Grade I) catching can easily progress to Grade II or Grade III or even to Type 5 (locking). Effective treatment is most predictable if undertaken at the earliest possible time and becomes rapidly more difficult if the catching is allowed to progress. Therefore, appropriate treatment undertaken when catching is still Grade I will be the most predictable. Treatment at this stage is most likely to avoid having the problem progress to a more complex and less treatable condition. At the risk of being redundant, identifying catching when it is at Grade I is only likely to occur if patients are asked very specifically about catching. They are unlikely to volunteer this.

Patient Type 6

Disc Displacement without Reduction

(Joint locking)

This condition is usually an end-stage outcome of a progressive process, typically represented by preceding Types 3 and 4. It can occur acutely, with the patient aware of a sudden and often significant limitation of range of motion (ROM). It can also occur in a more occult manner with very little awareness on the part of the patient. When occult locking occurs, the articular disc has typically previously been pushed forward over a long period of time. And although non-reducing, alteration of disc morphology may have occurred and little obvious change in the range of motion may be noted. However, if end-range deflection is noticed on the affected side, a comparative difference in the ability of one joint to translate may be seen. Locking of one or both TM joints may or may not be accompanied by pain.

It seems apparent that locking of the temporomandibular joint is well-tolerated by some patients, particularly if the locking has occurred without patient awareness, i.e. with little or no associated symptoms. Although degenerative changes within the temporomandibular joints (Type 6) are thought to be associated with progressive changes in the structural integrity of the joint (internal derangements), it is not clear to what degree non-reduction (locking) may predispose the patient to more rapid degenerative changes.

Three primary factors need to be considered is deciding how aggressively to treat a locked joint. TMJ surgery would be the most aggressive treatment option. The first factor that should be considered, quite obviously, is the degree of pain being experienced by the patient. The second, related factor is the degree to which the locked joint is interfering with function. An objective judgment regarding more aggressive treatment ( i.e. surgery) cannot be made until appropriate non-invasive treatment has been given a chance to reduce symptoms and improve function.

The third factor is the patient’s age. When a young person experiences an acute locking of the TM joint, because of their projected life expectancy it would seem reasonable to attempt to return the joint to as near normal function as possible to minimize the potential for problems in the future. There is also strong evidence that, in growing individuals, internal derangements have a deleterious effect on mandibular growth. TMJ surgery, when done using a thorough protocol, both pre-surgically and post-surgically (not just “cut and walk away”), may be indicated and can be very successful, with minimal complications in nearly all cases. This statement is made based on at least 25 years of experience using a very comprehensive protocol. When careful screening of patients and appropriate treatment protocols are used, both pre-surgically and post-surgically, I have no reservations about recommending TMJ surgery. A complete discussion of TMJ surgery, its indications and objectives, is beyond the scope of this article.

On the other hand, a patient in middle age, with limited symptoms and reasonable function may continue to do well with more conservative treatment. These two hypothetical patients just described represent the range of variables that should be considered. There is no single treatment protocol that is appropriate in all cases of a locked TM joint. TMJ surgery may be indicated if ROM remains significantly restricted, and/or if pain persists in spite of appropriate non-surgical treatment, particularly when these occur in a younger patient. Less aggressive treatment, such as a stabilization appliance and physical therapy may be appropriate and adequate in other patients.

Patient Type 7

TMJ Arthropathies

Several factors should be considered before undertaking treatment of degenerative changes in the temporomandibular joints. As previously discussed, degree of pain and impairment of function are primary considerations. Other factors, which can be difficult to assess, include causation, whether the degenerative process is quiescent or still active. The presence of significant joint sounds; i.e. boney crepitation, or significant changes on imaging are not, in themselves, an indication of a need for treatment. Joints with these findings, indicating significant degenerative changes, can be relatively stable. Therefore, indications of a need for treatment should be based more on pain or significantly altered function, rather than on joint sounds and/or obvious changes as seen on imaging. Significant occlusal dysfunction may be a contributing factor in degenerative changes. However, it is also possible for degenerative joint changes, with other etiology, to contribute to the development of a dysfunctional occlusion. Non-invasive treatment should always be considered first. If symptoms can be significantly reduced and a reasonable degree of stability can be achieved, this may constitute adequate treatment.

Patient Type 8

Aberration in Form

Aberration in form can include congenital or developmental disorders and most are not associated with orofacial pain. They can be categorized as agenesis, hypoplasia, hyperplasia and neoplasia. Hyperplasias and hypoplasias result in facial skeletal asymmetry as well as bifid condyles and other alterations in condylar form. Although often asymptomatic, non-painful deviation or deflection on opening may be seen. The altered form may be congenital, developmental, or secondary to trauma and is usually unilateral. Definitive diagnosis usually requires imaging. A screening panoramic image will be helpful in deciding what other imaging may be indicated.

Aberration in form, depending on its nature, can produce variations and/or limitations in functional jaw movements that might be misinterpreted as some other condition for which treatment might be considered appropriate. However, once the exact nature of this aberration is determined, usually by means of imaging, unless there are symptoms or other factors involved for which treatment would be indicated, it may be determined , in spite of some degree of limiting dysfunction, that no treatment is appropriate.